The truth about the 'Boriswave'

A staggering number of countries saw record migration numbers in 2022 and 2023. Was this global Human Quantitative Easing it all down to one man?

The Boriswave. The word of the week. The Reform Party has catapulted this once - very online - obscure term into the political mainstream. Everyone now has a snappy way to describe how Britain saw an unprecedented tidal wave of migration, triggered by policy changes made while Boris Johnson sat in Number 10 Downing Street, peaking in 2023.

But the media has been utterly silent on one curious but fundamental angle to this story. That Britain did not stand alone.

Far from it. The OECD’s global migration outlook report last year concluded “About a third of OECD countries experienced record immigration levels in 2023”, not just the United Kingdom but also notably “Canada, France, Japan and Switzerland.”

A JustinWave, Macronwave, Kishidawave, and Bersetwave. (Okay, hands up, I did have to Google whoever was in charge of Switzerland at the time.)

And across the Atlantic, the number of asylum applications in the United States (more than one million) surpassed those in European OECD countries taken together in 2023. It was America’s highest modern year for all kinds of migration, totalling three million arrivals according to Pew Research Centre. A Bidenwave.

Other countries peaked sooner. Germany’s wave crested with 1,500,000 net arrivals in 2022. Down Under saw higher numbers still, on a per capita basis. Australia - just a third as populated as Germany - accepted net arrivals at roughly 550,000 in the same year. Yes, that’s a Scholzwave and an Albowave.

In short, the 2022/23 ‘Boriswave’ of mass migration was not limited to Britain.

Either Boris Johnson really did secretly achieve his once much vaunted childhood ambition of becoming “World King”, or there’s something deeper going on here.

Aftershocks.

The years 2022 and 2023 were a strange time around the world. Developed countries were left reeling from the once in a generation impact of the Covid pandemic; a painful spike in public debt, an even more agonising spike in inflation, and atop it all faced the shock of wildly - extremely - liberalised migration policy.

While international public policy experts had on the whole failed to predict the wave of inflation that helped knock back all political incumbents as the world’s democracies went to vote last year, what those experts did detect was a concerning drop in labour market participation.

Of course, migration had fallen dramatically in all of these countries during the pandemic. Many simply banned people from entering. Some saw people flee. A part of what happened subsequently is a policy response to pump migration back from pandemic lows, but calibrated terribly.

Did any policymakers predict the sheer scale of the inflow that would result from their policy changes? Unlikely.

To momentarily dive into the world of metaphor, everyone can recognise how easy it is to exercise precise control when turning off a tap. By the same hand, it’s often far harder to control the flow when turning it back on. A rapid whoosh initially splurges out at at high pressure before the user of said tap gauges the resistance, reverses course, and - through subsequent managed turns of the knob - eases the whole flow back to manageable levels.

Just as with sticky taps in public conveniences, sticky migration policy levers in the corridors of power around the world are difficult to use.

But this was clearly not just about government after government trying to return migration to prior levels and getting it disastrously wrong. Most attempted to use migration to bolster the labour force in response to citizens dropping out too.

The domestic labour market drop out factor.

Around the world in the Covid years, people were paid to stay at home. Many were paid to do nothing at all. Many liked it.

Some young people were discovering a perverse joy in staying in a darkened room - diagnosing themselves with various mental health incapacities or a psychosomatic form of ‘Long Covid’. Suddenly people were used to a life claiming from the state. And they liked it.

On the other end of the workforce age range, people simply retired. Many people in their 50s and 60s decided life at home was just nicer. No more busy commuter trains or infuriating commuter traffic. Lovely warm summer days in the garden had - for some - made lockdown the time of their lives.

Economic inactivity amongst the over 50s shot up after the pandemic. People had considered what they were living their lives for. Perhaps things would just be nicer with less income and less work. The assets they owned had inflated in value so much that they would still hand down a king’s ransom as an inheritance to their children. So why did they need to work quite so much?

At both ends of the labour market, people decided to work less. Many decided to give up on work altogether, and settle in to a life of leisure.

Enter the government.

Suddenly, lockdown is over, but people are remaining out of work. In Britain there more than a millions job vacancies. Far more vacancies than people seeking jobs. What to do? Well the man in Whitehall, (or Washington, Wellington, or Warsaw) might decide to simply top these people up in the mistaken belief that human beings are all fungible.

In response to labour shortages, in the United Kingdom our Shortage Occupation List was expanded to comical degree. Everything from plasterers to share fishermen were added. The new points based system was effectively bypassed. The Health and Care Worker Visa was massively expanded to include all social care roles. And this thinking was not unique to Britain.

Canada allowed temporary workers to bring along their spouses and working-age children starting in 2023. France abandoned rules preventing firms hiring from abroad without first having to advertise domestically for certain roles. Germany lowered migrant salary thresholds. Australia extended post-study work rights. Japan added nine entire industries to its skilled worker list.

The lights flash red. Panic in the chancellories. It appears that there are huge shortages, so the civil services of the world - having shared the same economic textbooks and best practice conferences - all tell their ministers to open up. To engage in Human Quantitative Easing. To replace inactive domestic workers with foreign ones. To suppress wages and avoid inflation traps. The same advice from the same people who rotate through the same jobs at the ECB, IMF, and World Bank Group.

And who were the politicians to tell their experts (many of whom had worked in organisations with impressive acronyms) “no”?

Well, politicians with greater backbone might have made the following argument: human beings are not fungible. Of course, everyone is individual, other than identical twins no two human beings are quite alike, thank goodness. But we can inform public policy by looking at group averages. Research shows that people coming from different parts of the world and wildly different cultures have remarkably differing contribution and dependency levels.

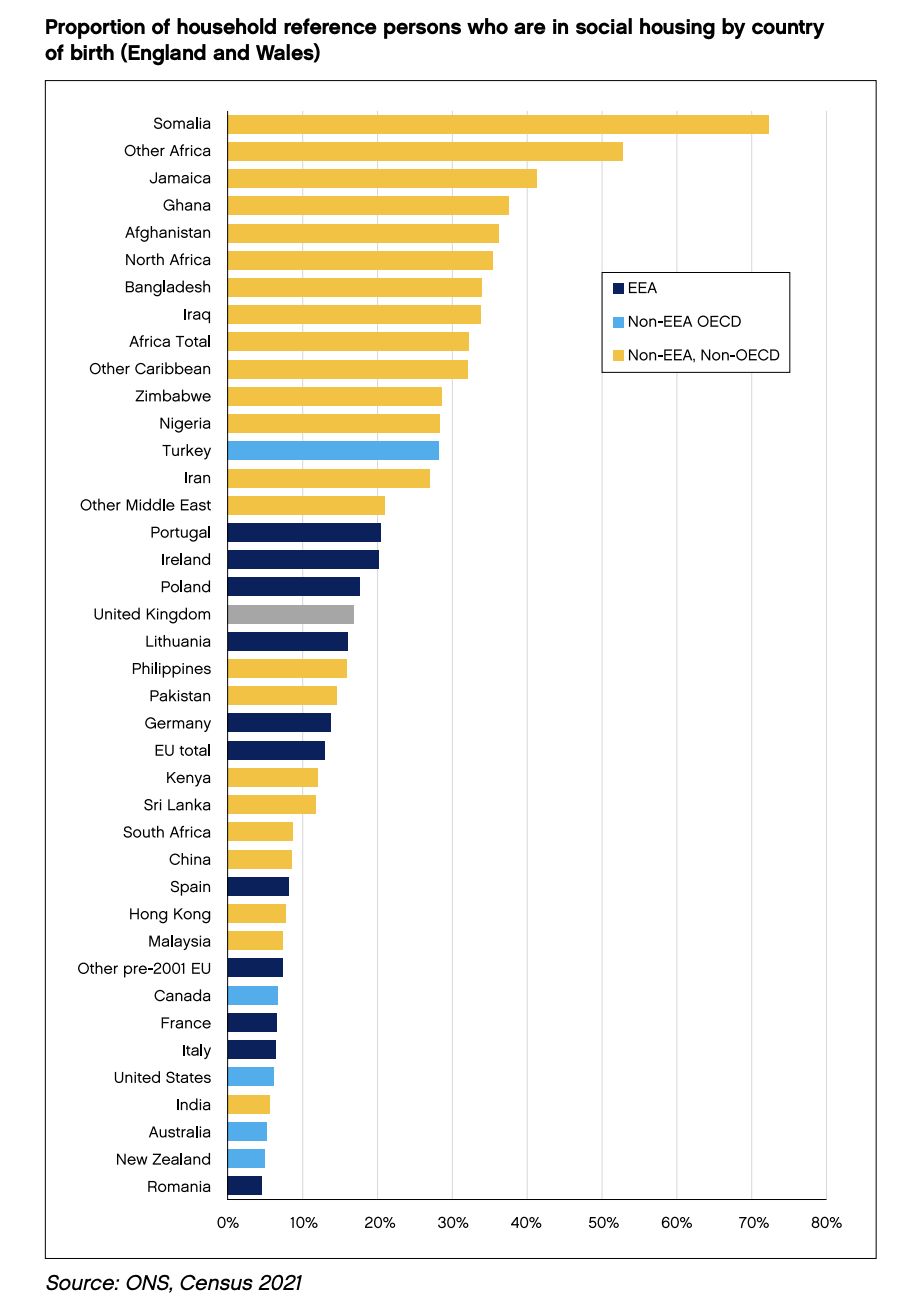

Just 6% of people from India living in the United Kingdom reside in social housing. Compare that to 15% for people from Pakistan and 34% for people from Bangladesh. The average for people from Africa is 32%. That ranges from 9% for South Africa to an astonishing 72% for people from Somalia.

A rational migration policy might have looked to have stricter criteria for those looking to migrate from Somalia, Jamaica, or Ghana than those from Australia, New Zealand, or Romania (social housing rate <6%).

Of course social housing is just one metric. Crime statistics could be another. Any form of data-led discrimination. Rules to ensure economic benefits and cultural cohesion. But no such rationality won the day.

Asylum.

The elephant in the room so far of course has been that the end of Covid also coincided with mass refugee events. The disastrous Afghan withdrawal. The war in Ukraine. And - specifically for Britain - China’s political annexation of Hong Kong. It’s estimated that around 180,000 Hong Kongers with British National (Overseas) passports moved to Britain on the BN(O) asylum scheme, established by Boris Johnson.

Around 255,000 Ukrainians came to Britain too, though continental countries saw far higher numbers. Meanwhile, war in Syria continued to contribute to massive migrant flows across Europe. In the New World, crises in Venezuela and Colombia created millions of displaced people seeking stability elsewhere. Almost eight million Venezuelans have now left their country - ravaged by socialism. That represents more than one quarter of their national population.

There were also less conventional waves of people mixed up with the genuine refugees. Unlike migrant flows caused by famine, poverty, and war - the 21st Century has seen an entirely inverse phenomenon across African countries. When particularly sub-saharan Africa was near subsistence poverty, few had the money to travel. As these countries move up the income ladder - to less extreme levels of poverty - suddenly more have the means to move. And move they do.

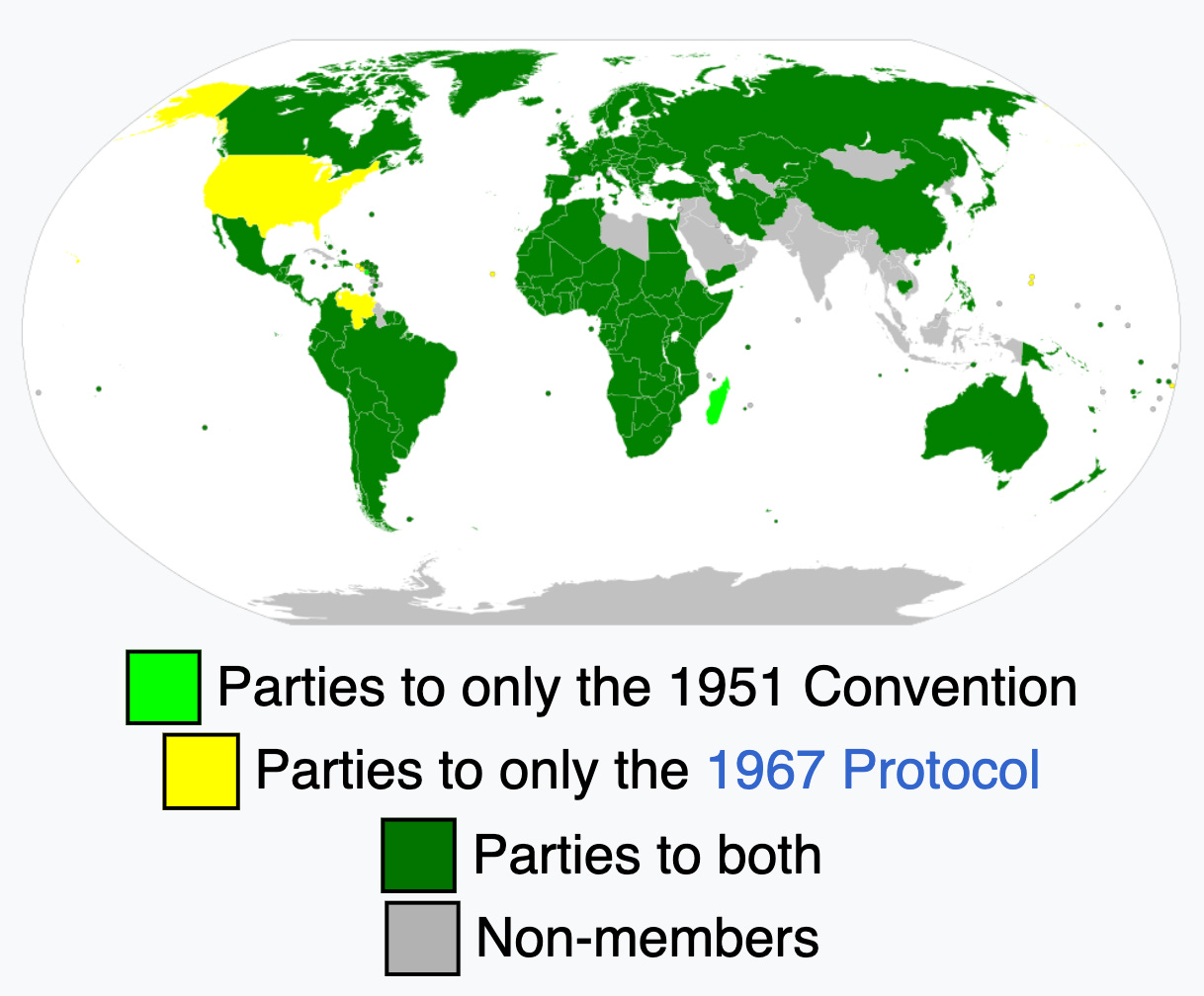

Many states are legally helpless to accept the less genuine asylum seekers. They are party to international agreements that have been interpreted broadly, and hand enormous power to the judiciary to adjudicate.

Many who claim oppression are in reality - entirely rationally - seeking a better life in a higher income country. The international refugee convention most of the globe signed up to in 1951 could not foresee a world where billions of people had the potential means to move thousands of miles in search of greater economic opportunity.

Under the terms of the 1951 Convention, arguably billions of people in the world today could qualify for refugee status. Very few countries meet the bar for what we might expect as human rights. And under its terms anyone who can make it to the shores of a convention signatory state can claim asylum as soon as they land. By law, their claim must be heard. No country party to the convention has found a real solution to control the modern flows that this right encourages.

Choices - and lack of choices.

These are just some of the political and economic factors that led to what many governments now see as a global error of judgement. An international moment of groupthink that overwhelmed institutions and fanned the flames of populist movements across the world.

What lesson can we draw from the Boriswave? That Boris Johnson deliberately sought net migration reaching 906,000 people in 2023? No. While Johnson was clearly more of a liberal on the issue than Theresa May or Nigel Farage, he wasn’t an extremist.

What we can glean from the Boriswave in its international context is that rather than pushing extreme policy, Boris Johnson was passive in the face of groupthink. The machine did what the machine does. And it churned out the same policy in most developed countries.

While this week we all learned about the Boriswave, we should take note of the Bidenwave and the JustinWave. The Macronwave and Kishidawave. The Scholzwave and the Albowave. The countries around the world that collectively threw open their borders - to engage in the quantitative easing of people - only to reverse ferret two years later.

Is it truly likely that Boris Johnson exercised control or influence across every corridor of power around the globe, with Disraelian deftness and diplomacy bending the great powers of the world to his will?

No. It is my contention that we reverse the implied cause and effect of Boriswave nomenclature. That the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is no longer the globally hegemonic mover and shaker of centuries past. That World King Boris was not. And that instead, it was our Prime Minister moved and shaken.