The social cost of closing the income gap

How today's hike in the minimum wage will leave more people feeling poorer

Happy first of April. Today’s famous date means lots of jokes, some funnier than others. The least funny of all is the fact that many policies from Rachel Reeves’ first budget now bite.

The 9% national insurance tax hike, making it more expensive to employ everyone - but particularly more expensive to employ the lowest paid due to the slashing of the threshold at which this tax is introduced from £9,100 to just £5,000.

The abolition of the Non Dom rule, a populist policy change that has sent some of the richest people in this country packing, shifting more of the tax burden to those of us who aren’t billionaires.1

The 6.7% hike to the National Living Wage, something that used to be more sensibly called the minimum wage but was rebranded by the Tories for no reason in particular other than to confusingly compete with a voluntary scheme that the Living Wage foundation now have to call the Real Living Wage.

It’s easy to see how the first two of these policies, both tax hikes, hit working people. Employers pass on higher employment costs to their employees, in the form of lower wages than they otherwise would be receiving. The hyper mobile super-rich up sticks and leave the UK, taking the tax they would have paid (and often many of the people they employ) with them.

The third of these policies, however, is often spoken about as if it is an unalloyed good. A rise in the minimum wage, cheer the MPs. On left and right. Time and time again.

In times of austerity politicians can look very generous simply by raising the price floor for employing people. After all it’s not going to look like government spending or appear to cost taxpayers’ money.

The arguments about the ensuing unemployment effects are well rehearsed; the fact is that a higher minimum wage does nothing to help more people onto the employment ladder, it simply removes the lower rungs. All else being equal, raise the cost of hiring people and fewer people are hired than otherwise would be.

There is another effect, however, that is not spoken about. A socio-economic effect. And that’s the impact on people earning average salaries.

Earlier this year the Resolution Foundation produced a fascinating piece of analysis.

“Graduate salaries have stagnated while the minimum wage has risen, leading to convergence between the two. Two decades ago, the median graduate in a ‘graduate job’ had a salary 2.5 times that of a minimum wage worker, by 2023, the typical graduate earned 1.6 times a minimum wage worker.”

Since the introduction of the minimum wage, both Labour and Conservative budgets have raised the rate relative to median graduate earnings. Some budgets, for example the Tory post-election budget in July 2015, introduced wage floors that were even higher than the recommendations of the Low Pay Commission - a body set up by Tony Blair to advise politicians on minimum wage rates to minimise unemployment effects.

The result is the chart above, showing the stark convergence the Resolution Foundation wrote about.

Once you take into account the 9% higher rate of income tax until their ‘loan’ is paid off, it’s easy to see how many graduates barely earn more than someone in a minimum wage job. And as British graduate wages remain low compared to economies that are actually experiencing economic growth, today’s minimum wage hike continues this trend.

Since the significant hike relative to graduate wages in 2015, the line between skilled and non-skilled wage rates has become ever more blurred. A graduate data analyst or accountant might have expected to be paid significantly more than someone pulling pints or operating supermarket checkouts.

Yet thanks to stagnant productivity and low growth, graduate wages have been flat.

Higher up the income scale we feel the effect of this lack of productivity growth. But if you’re on the lowest legally permissible wage, your salary has been pumped up by government diktat as if there were no productivity crisis to speak of.

This has of course had knock on effects for prices. If bar, restaurant, or cleaning staff have to be paid more, the price you pay for their services is higher too. So while people on middle incomes see their wages stagnate, the nice things in life like going out to eat or even just going to the pub get more expensive.

There is a clear psychological belly punch too, and it’s just as depressing. Skilled workers who have invested years of their lives in education and training have seen wage rises far smaller than the minimum wage hikes, flattening out distribution to the extent that suddenly we find ourselves in a position whereby teachers feel like barmen.

Consistently governments of all colours have taken the easy but cowardly move to hike the wage floor ahead of, rather than commensurate with wage rises further up the chain. Ahead of the hoped productivity growth that will at the end of the day have to pay for it all. And so the minimum wage creeps closer and closer to the average wage.

There is one man who might just be delighted by all of this, however. Treasury minister Torsten Bell.

Bell ran the Resolution Foundation from 2015 up until he quit to land a safe Labour seat in Wales and become a Labour MP last year. Despite having previously served as Ed Miliband’s director of policy, over the years successive Conservative governments fell over themselves to win approval from Bell’s Resolution Foundation. Approval came in the form of distributional analysis charts - modelling how any policy might impact different income groups.

If the chart showed a policy change helped those on the lowest incomes most, it won plaudits. If however a policy helped rich people more than it did poor people - even if everyone got better off as a result - then such a policy was scolded as heretical. Most Tory budgets therefore, toed the line.

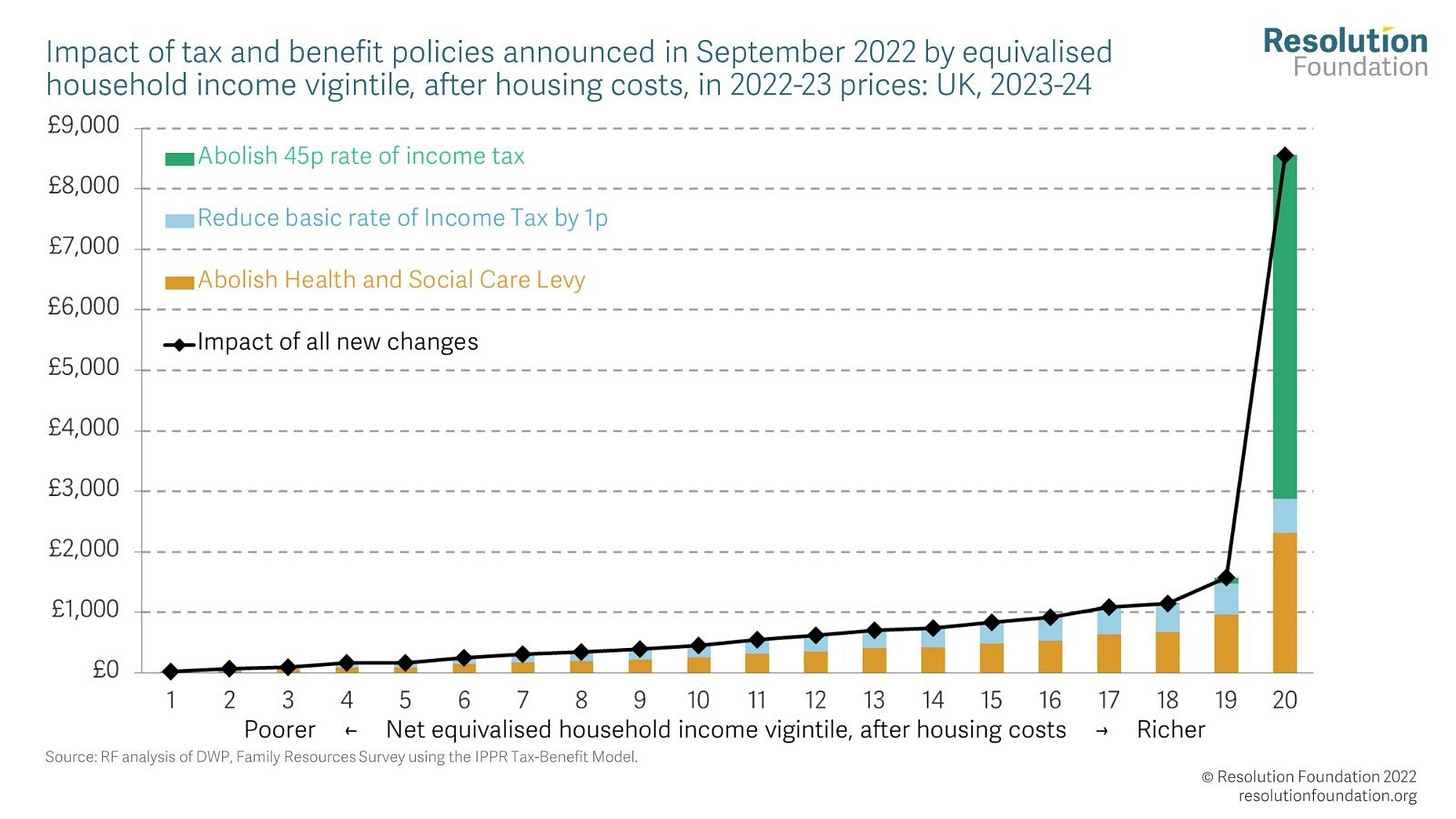

This was the Resolution Foundation’s chart that was presented to Liz Truss on the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg programme, that helped force the 49 day Prime Minister into her first u-turn, hastening the end of her troubled premiership:

The political attack was that rich people would get richer due to the abolition of the absurd 45p income tax rate - a tax cut the CEBR assessed to be “at least self financing”, and that the IFS said “might plausibly cost nothing at all”. Consequently returning our top rate of tax back to Blair era levels, even at no loss to revenue, became impossible thanks to an unhealthy obsession about the gap between rich and poor, almost to the exclusion of any other consideration.

This has, undoubtedly, been bad for growth.

All non-Truss conservative governments have been so preoccupied by maintaining and even increasing2 the level of income equality, that even returning top tax rates to the level they were at back when this country experienced economic growth was seen to be undesirable.

Obsessing over the gap between incomes in preference to an obsession regarding the absolute level of incomes might make inequality campaigners happy. It might block off an avenue of attack from your political opponents. But it might also make the country, eventually, feel miserable. It might make graduates feel like they might as well be pulling pints.

Back in 2023 Stian Westlake wrote a tongue in cheek blog for Works in Progress about how successful the UK’s anti-growth story has been. Perhaps now should be a moment of celebration too. “We did it, we narrowed the gap! Graduates and minimum wage employees are now more equal than ever before!”

And don’t we all feel better off for it.

Yes, contrary to popular belief non doms do (did) pay tax. On any income earned in the UK, British tax was applied. The tax relief was applied only to income earned overseas.