The Great British Baby Bust

Below replacement fertility rates are crippling our society. Happy Christmas.

It’s the most magical time of the year again. A festive time for seeing family, drinking too much, and thinking about the birth of the baby Jesus. In other words what better time of year to talk about the fertility crisis.

When could there possibly be a more appropriate time to mull over the metaphorical King Herods that are causing this crisis - principally the cost of childcare and the cost of housing.

It may be a trite news hook for this essay, but how else am I going to talk about what we really don’t discuss enough as a country. How we simply aren’t having enough babies.

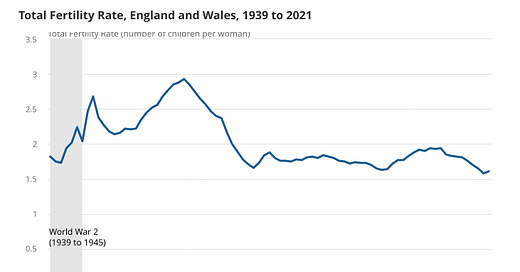

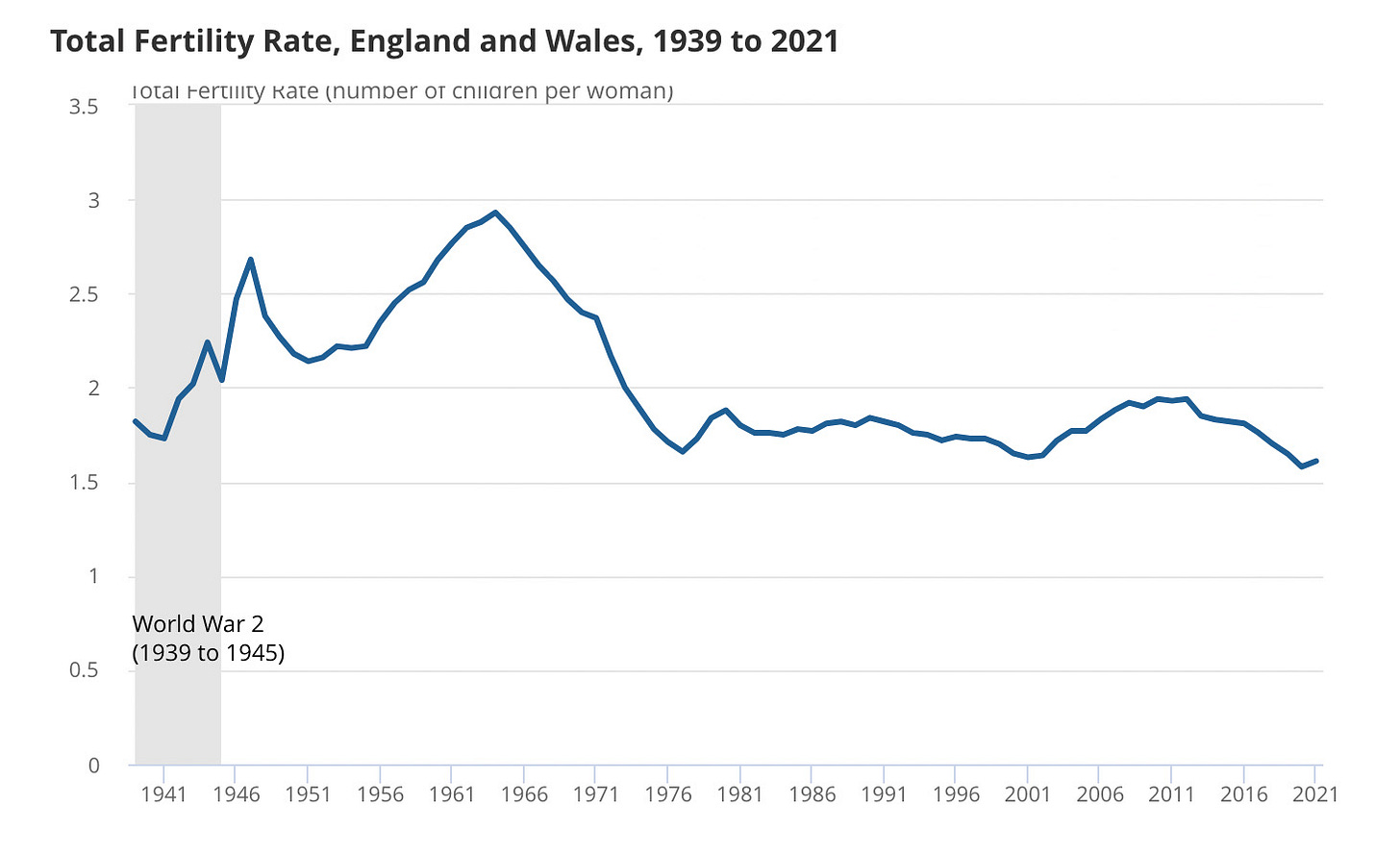

First, a gentle stroll through our demographic history. We have an ageing population. And before we get into the financial and societal issues this unfortunate fact leads to, it is important to note that we haven’t seen the worst of it yet. Not by a long shot.

What some may have missed about our own ageing population is that unlike in the Untied States where their baby boom came about immediately after the war, in the United Kingdom the bulk of our baby boom came much later.

First, there was a shorter spike in births in the immediate aftermath of the war, no doubt fuelled by enthusiastic returning servicemen, and reunited couples vigorously celebrating our victory. Yet this patriotic ‘lie back and think of England’ spike in births did not last long. In fact it crashed pretty much as soon as the reality of postwar life set in.

There wasn’t any money. Britain’s time as a superpower had ended. Swathes of many of our largest cities lay in ruins. And rationing continued until 1954.

Things were so grim that the Conservative Party won the 1951 general election through campaigning mainly on the issue of opposing rationing - a political choice that the socialist Attlee government pursued years after the war in what might properly be described as an enormous endeavour of levelling down.

Our fertility rate only experienced its significant, sustained increase over a decade after the war. Perhaps as people felt more improvement in their standard of living, fertility improved. Perhaps they just liked the Beatles. (Or if we want to be strictly time-accurate, The Quarrymen). Whatever the cause, through the late 1950s and early 1960s the birth rate grew substantially, peaking at 2.93 children per woman in 1964. This was our real baby boom.

Source: ONS Births in England and Wales: 2021

The proper peak in births not arriving until 1964 changes this discussion in the UK compared to other countries. Unlike the majority of American baby boomers who have been enjoying retirement for some time, significant numbers of the biggest block of British boomers are only due to be approaching retirement in the coming years, with significant knock on effects.

By 2066 the UK will be home to an extra 8.6 million people aged 65 years and over, a cohort equivalent to the entire population of London.

The proportion aged 85 and over is projected to double by 2041.

And treble by 2066.

And with the unfunded welfare commitments that successive governments have made, that’s a problem.

Of course, there are many benefits to the UK being home to a larger number of older people than we have ever had before. People living longer, healthier lives is a good thing. Less early death benefits society. Bigger families are often stronger families, allowing for sustainable non-state based support networks. And, of course, a larger market of older people is a vital boon to the struggling sherbet lemon industry.

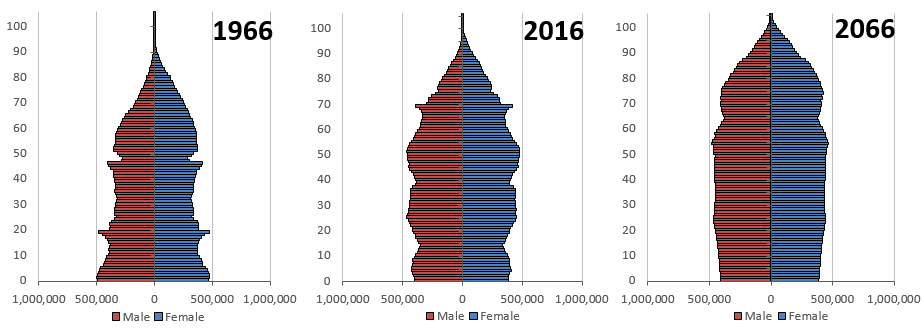

The demographic problem only arises when the famous ‘population pyramid’ becomes inverted. A society with more old people in it isn’t the issue, an ageing society is. It’s not the number of older people we need to be concerned about, but the ratio of young to old. It’s not the boom that is bad, it’s the bust.

Pensioners today receive £9,627 a year through the state pension. All twelve and a half million of them - from those in real poverty to the wealthiest millionaires. And considering a worker on the median full time salary of £33,000 a year pays just £2,627 in National Insurance (which of course is supposed to pay for pensions, as well as funding our NHS after all), it’s easy to see why we need significantly more people in work than those that are out of it.

And all too sadly, this seemingly obvious statement needs to be spelled out. As things stand, far too many people have been living under the surprisingly widely held misapprehension that their pensions have already been paid for.

That they have already filled up a safe deposit box somewhere for their own state pension.

Unfortunately for all of us, National Insurance is not a savings account. As we’ve seen demonstrated in the numbers above, it’s a Ponzi scheme. Plain and simple. There is no pension saving pot that this money is paid into. Instead, the cash raised through National Insurance is spent at the time it is raised. It simply acts a devious double income tax.

As with any proper Ponzi scheme, the National Insurance contributions of those retiring now have long since been spent. Consequently, in order to fund growing demand for important things like pensions and NHS care without hiking taxes, there has to be a constant growing supply of people paying for them. When the 65 year olds of today were paying their National Insurance in decades past, it was funding the social services of the retirees of decades past. And there were many fewer of those to pay for, relative to the working age population. In short, the population pyramid was the right way up.

The maths worked. There were many more people in employment than out of it.

Retirees are of course by definition at the end of their working lives. They are people who have stopped putting into the collective pot and consequently after decades of work understandably expect to be able to take out of it. Which they do in spades. The bulk of healthcare spending goes on older people, and state pensions make up the largest chunk of the welfare budget.

Up until now, mainly thanks to sensible state pension age reforms, the proportion of Brits who can claim state pensions has hovered around 300 per 1,000 working age people. According to the ONS, by the 2040s this will have boomed to the mid 370s per 1,000. And by 2066 it will touch 400/1000.

An incredibly expensive trend, especially when you consider how state pensions have been rising faster than the pay of those in work in recent years.

Source: Population estimates, State Pension Age Factors, Principal population projections, 2016-based, Office for National Statistics

If a shrinking pool of working age people has to fund a growing pool of people of retirement age, that working age pool ends up being squeezed more harshly than ever before. Worse services. Higher taxes.

In fact the results of an inverted population pyramid are becoming ever clearer:

Taxes rise to fund a creaking welfare state.

The NHS seems overwhelmed.

The labour market is suffocatingly tight.

And all this, despite migration being higher than it has ever been before.

And we have to remember that all of this is before the biggest wave yet of baby boomer retirees hit us. (Though much of our labour market tightness is due to a significant increase in people taking early retirement after the pandemic.)

So where does that leave us? With a clear looming problem, certainly. But also a potential road out of the worst of it. Population gaps have been plugged in recent years through increased migration, without which taxes would likely be higher still. Yet ad hoc gap plugging is not an ideal way to run an economy. It carries risks, not least of all democratic backlash and therefore the potential for a sudden drop in the flow of working age people. Reliance on migration also carries with it the arrogant assumption that people will always want to move to the UK. Which, given our sluggish growth, profound housing crisis, and rising tax burden, should not necessarily be taken for granted.

The long-termist goal here must refocus, recognise the good migration can bring, yet be much more proactive in removing the many barriers to having babies.

Procreation leads to wonderful things. More people means more human capital. One of the key ingredients underpinning economic growth. One of the reasons the United States grew to become the world’s undisputed economic superpower in the last century. Wealth and jobs are not zero sum. Greater human capital leads to greater innovation, business creation, and problem solving.

It’s worth remembering at this point too that there is plenty of space for more people in this country. Perhaps this is a tangent for another week, but the UK is one of the largest islands in the world, with some of the lowest density cities when compared to other major countries. If London had a similar gentle density to that of Paris, it could house almost double the population, in buildings that look a lot nicer too. And even as things stand with our criminally inefficient use of space and low density urban areas, just six percent of the UK is actually built on.

Fundamentally if we had higher fertility, if we had stronger sustained population growth, the challenges our social services face would be far smaller. With more people of working age in work, the healthcare and pension requirements of an older generation can be properly funded.

The trend as it stands is overwhelming. It’s a bumpy picture, but it’s bumping its way to inverted pyramid status. There is a wave of older people approaching retirement, and our ‘youth deficit’ is setting in train a host of economic and social issues. From higher taxes to worse healthcare, lower growth, and generational resentment.

Source: Population estimates, Principal population projections, 2016-based, Office for National Statistics

Despite a mini fertility bump in the early 2000s, we have not managed to reach replacement ratio - over two children per woman - since 1973. Since the financial crisis our birth rate has been in pretty steady decline. And indeed despite forecasts of a Covid lockdown baby boost by some, this never materialised.

Perhaps it was the countless viral moments of zoom-crashing children that put potential families off. Perhaps banana bread has hitherto unknown contraceptive qualities. Or perhaps more simply, being locked indoors while the economy is in free fall and the future uncertain is neither the most stable environment for family planning, nor particularly sexy.

Whatever the truth of it, Britain still isn’t bonking. Or perhaps it is, just not particularly productively.

As I hope I have explained so far, this really does need solving. But there is more to it than funding our creaking welfare state. Indeed there is more to it than the need to lower the excessive tax burden which next year is rising to its highest point on record. The fertility crisis has to be tackled too, for reasons that go beyond economic calculations. More babies being born has the potential to enhance the human happiness of new families in the United Kingdom as things stand.

One of the most remarkable points to note in this conversation, indeed that should be far more widely known, is that the rate of fertility outcomes is a statistic distinct from and separate to the rate of fertility intentions.

The number of children that women are having and historically have been having in the UK is lower than the number of children that they want to have. Studies have suggested that this gap is wide enough to be is the difference between achieving replacement level fertility, and not achieving it. We can be fairly confident in stating that families still want to have more babies, they still want to grow, they just don’t feel able to do so. At least not in the numbers that they originally intend.

And that leads us to ask one big question. Why?

Women who want to have children aren’t having the number that they want to have. Lack of interest in starting a family can’t be behind that. Evolving forms of relationships can’t be behind that. The existential angst of climate doomerism can’t be behind that.

It seems clear that there is one key culprit holding back human happiness in this area. When it comes to our fertility crisis, the chief metaphorical King Herod here is cost.

Cost of caring.

Cost of housing.

Cost of falling behind in the workplace.

Childcare in the United Kingdom is amongst the most expensive in the world. The UK, and specifically England, has the strictest teacher:child ratios in Western Europe. Burdensome regulations, though well intentioned, have driven costs up to unaffordable levels for many families, leaving many with the stark decision that leaving the workforce to care for their own children might be an economically rational thing to do. This is bad for families and bad for taxpayers.

In order look after toddlers in England, the state enforces a mandatory teacher:child ratio of 1:4. In Scotland it’s 1:5, the Netherlands 1:6, Ireland between 1:6 and 1:11, France between 1:8 and 1:12, whereas in Denmark, Germany, and Sweden there are no such restrictions. Childcare services can work out what is best themselves.

If the UK were to liberalise its childcare rules it’s easy to see how the startlingly high costs could begin to fall. Similarly a fresh approach to how parents share the responsibilities of childcare would certainly be welcome.

Yet childcare and shared parental leave are perhaps a smaller pieces of the pie when compared to the elephant in the room of just about all UK public policy.

The housing crisis.

New families used to be able to expect to buy a house in their 20s. Now, the average age at which Brits finally get onto the property ladder is 34. The increase in house prices compared to average wages has been nothing short of astounding.

And there is only one reason behind it. We aren’t building anywhere near enough houses. As former Housing Secretary Simon Clarke put it earlier this month “since the 1950s and the 1960s, the rate at which we have expanded our housing supply has halved even as the population has risen.”

There is so much more to say on this matter, but put simply as the market is crying out (through the most obtuse, glaring, loud, singing and dancing, bedazzling and bejeweled price signals imaginable) for more homes to be built, politicians have clogged up the market mechanism - refusing permission to build the homes the market is trying to build.

In a world where our planning system was more rational, less arbitrary, more rules based and rested less on the whim of local government, the price mechanism would be working in the way it does when not stymied by the state. The profit motive would motivate those who want to make money to build homes where it is most profitable to do so, in turn bringing dow the price. Economics 101.

We would have many more homes where they are most needed. Yet twice in the last decade sensible attempts to unstick the planning system have been brought forward by the government, first by Nick Boles and secondly by Robert Jenrick. And twice in the last decade these attempts have been defeated in the Commons by what one might describe as an anti-growth coalition, comprising all political parties.

As a consequence of decades long political failure, and the triumph of those who campaign against development, too many couples are now sharing flats with others well beyond their early twenties. Too many married partners can’t afford an extra room for a child. Too many adults are even living with their parents.

It is clear how this sort of shared living, a lack of spare bedrooms, and ultimately the fact that those who did not have the good fortune to buy property decades ago have to pay so much for so little, all impacts the ability of couples today to have children.

Less disposable income means tougher work life balance choices, and less cash for childcare too.

Cramped, expensive living conditions cost not only ever and ever higher proportions of people’s incomes, but in too many cases they cost potential children now too. It’s the human cost of those campaigners and politicians preventing new homes being built. They are preventing new families from developing and growing. They are stunting not only economic growth, but human happiness too.

It’s clear why many families choose to not raise children like this. Choosing to wait until it’s suddenly too late. Choosing to stop at a number of children that was less than they desired. All on the the grounds of cost and care.

It’s a miserable situation. But it is only through spelling out this misery that policy to make things less miserable can be realised.

Families are sadder than they should be. There is less life, less joy than there could be. There is less human capital and innovation than this country deserves. And the social security structures upon which we all expect to be able to rely are creaking under weight of bad policy choices, decades in the making.

And looking at those population pyramids, things are currently on course to get a lot worse.

So we need to talk about the fertility crisis. Above all we need to deliver urgent supply side reform to childcare, and to housing. We need to create the most positive possible environment for families who to want to have children to be able to assuredly make that choice.

This Christmas it’s time to slay the costly King Herods causing this crisis, liberalise childcare, and try to ensure that in 21st century Britain we could maybe set our housing standards sights slightly higher than that of the stables of Bethlehem 2,000 years ago.

The problem with this analysis is that ignores the other side of the coin, which is nett immigration.

Any fertility decline in the aboriginal population is more than compensated for by the immigration of Gurkhas, Hong Kongers, Ukrainians, Europeans with a post-Brexit right of residency, and any other waif and stray who simply overstays his visa (if he even bothers with that). Anyone who uses the London buses will be aware of the huge number of people not speaking English. Some 40% of the population of London is supposed not to have been born in the UK. Immigration adds to the pressure on hospitals, schools, and the health service, which must in turn be funded out of general taxation - and that is borne most heavily by those already invested in society.

For a generation now, both the cost of living and quality of life measures have been declining so as actively to discriminate against the native population's fertility.

Lack of housing? Nothing to do with the 10-15million extra people added here in the last 20 years - the biggest mass migration in history (thanks Blair and the New Conservatives)?

No places in schools? NHS broken?

Might be a clue?