If you didn’t feel a little for a teary eyed Rachel Reeves yesterday, you have a heart of stone. I’m not going to reproduce the images here, we’ve all seen them, and they have already become defining pictures of this government.

Whilst the Treasury has been briefing about an unspecified personal matter, and some have noted a strange altercation with the Speaker, the clear wider context is this week Reeves became a ChINO. Chancellor In Name Only.

“I'm under so much pressure”, Reeves reportedly said to a colleague before taking that fateful seat in the eye of the country.

Public pressure had already forced a u-turn on winter cruise fuel payment cuts. Then Labour backbenchers rejected Reeves’ pleas to trim ballooning benefits spending. The days long double u-turn fiasco of the Benefits Bill shaved hoped for savings down from £5 billion to £2.5 billion, and finally to minus £100 million.

The climbdown is humiliating for the Prime Minister, but a clear personal blow to the Chancellor. It is she who will have to return to the despatch box in the Autumn and announce billions upon billions in higher taxes.

With every PIP benefit reduction stripped from the PIP benefit reduction Bill, all that remained of this once-flagship piece of legislation were tweaks to the health element of Universal Credit - saving roughly £1.7 billion - paired with a rise in the basic UC rate that adds about £1.8 billion in extra spending. The government rushed this Bill to a vote in a desperate attempt to save money, and ended up spending an extra £100 million instead.

As the tearful Chancellor stared into the middle distance yesterday, the markets decided she looked like a defeated woman. The Prime Minister refused to say she would still be in her job come January, and sterling took a sharp drop. The price of servicing government debt climbed to new highs.

The economist Julian Jessop estimated the whole sorry show knocked about 1% off the value of the pound, and added 5 to 10 basis points to the cost of UK government borrowing.

The Welfare State We’re In

The markets expressed what the rest of us can see. First the public and now Parliament have a clear and insatiable desire for ever higher public spending, without the revenue to pay for it.

Thanks to the climbdown, between today and 2030, the amount spent on disability benefits alone will balloon by £13 billion. That’s an extra £1000 that needs to be taken from 13 million people in tax. The Chancellor had hoped to slow the growth in the budget to a mere £8 billion increase, but both Reeves and Starmer failed to convince a largely innumerate lump of Labour MPs of the necessity of these cuts.

Shortly after the government’s humiliating climbdown, HuffPost’s Kevin Schofield reported one Labour MP as being heard saying: “I don’t understand why this means tax rises when it’s only a few billion pounds.”

The chaotic coalition that makes up the Labour Party hasn’t been able to come together to agree that there is something fishy going on. This despite the alarming data showing how enhanced PIP payments (that’s the highest level of PIP, including a mobility component you can trade for a free brand new car) have more than ballooned between between 2019 and today:

Autism: 26,256 up to 114,211

Anxiety and depression: 23,647 up to 110,075

ADHD: 4,233 up to 37,339

Obesity: 2,346 up to 11,228

Labour MPs have failed to come together and recognise the insanity of a system that has led to the free and tax exempt car scheme Motability (through which enhanced PIP recipients can choose brand new cars for free, or massively discounted models of swankier cars including BMWs, Mercedes and Audis) taking up almost one in five new car sales in the UK.

Motability cars even come with insurance, servicing, and breakdown cover all included so not a penny has to be paid by an enhanced rate PIP recipient for their new car, fresh from the showroom.

It’s a mess. It’s all a mess. Thousands more are signing on to these benefits every day, screened only by an assessor at the end of a telephone line who is actually financially rewarded for approving more cases more quickly.

To her credit, Reeves has time and again tried to do the right thing. She has tried to cut universal welfare to a wealthy cohort. She tried to curb the exploding benefits bill. She wanted her first tax hiking budget to be her last. To meet fiscal pressures with spending restraint rather than yet more tax hikes on a country that has never been taxed more. Extreme Labour MPs who who can’t wrap their head around what the word "billion" means have made that impossible for her.

But something else has too.

It all comes down to growth

The miserable state of British politics cannot be separated from one gruelling fact. The economy has flatlined since 2008. Unlike in the United States, productivity (output divided by hours worked) has never returned to its pre-crisis trend. Despite repeated Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts that Britain will return to higher productivity growth, we have not.

Which all leads to this thoroughly depressing ‘hedgehog chart’ - produced by J. P. Morgan. It shows expectation after expectation of forecasted higher growth compared to the flatlining reality.

Had productivity grown, tax revenues would be higher by tens of billions of pounds. The Chancellor wouldn’t necessarily have felt the need to borrow to the very limit of her fiscal rules - a strategy so precarious that it leads to the most minor OBR forecast revision to cause budget crises for the government.

Had Reeves (and frankly the Tory Chancellors before her) felt able to leave a bigger fiscal buffer - or heaven forfend a balanced budget - no one would think the OBR was running the show. The much-hated quango is only as influential as it is today if the country is at the very brim of its borrowing budget.

In a world where the Chancellor doesn’t see it as his or her duty to borrow to the hilt, the supposed power of the OBR vanishes in a puff of smoke. Suddenly it doesn’t matter that they have revised their notoriously unreliable growth forecasts, or that some world event has sent revenue south. The closer to the borrowing limit a Chancellor becomes, the more powerful the OBR appears to be.

And that, in the end, is why the Chancellor was scrambling to find the now-abandoned cuts.

But just imagine how different things would be if when it comes to growth, Britain looked less like Europe and more like America. Imagine the Chancellor had strong growth and consequently more options.

Far fewer crises would dominate the news cycle. And the slush fund of growth induced cash would grease the wheels of serious public sector reform. Trying to reform public services with only sticks and no carrot does not a happy public sector make.

It is simply staggering to see the difference in productivity growth between the United States and Britain since the crash. Through the 2000s to 2008 the trends of the two countries matched one another. And since the Global Financial Crisis there has been a great divergence.

Perhaps most interestingly of all is the way European economies and the United States respond to a recession. See in the FT’s graph above how productivity fell in Britain and Europe in 2008 and 2009, but soared in the United States.

America’s weaker employment protections mean in recessions firms let more people go, becoming leaner and more productive. Meanwhile in Europe jobs seem to be prioritised above everything else, leading to bloated zombie firms and markedly lower labour productivity.

The European fear of allowing companies to let employees go necessarily reduces dynamism in an economy. Sticky workers means less chopping and changing, less discovery of higher productivity or better matched jobs. This effect is about to get worse thanks to Labour’s Employment Rights (wrongs) Bill.

It could well be that Britain prioritised keeping zombie firms afloat over the creative destruction necessary for productivity gains. But there are other factors to consider too.

The London Problem

Stay with me here because we are going on a London-centric tangent. It’s hard to stress just how important London is to the British economy. The average salary in London is £10,000 a year higher than the average salary in the North East of England. If more people from the North East chose to take jobs in London rather than Newcastle, their measured productivity would increase significantly - they would earn far more money for the hours they work. And the Treasury would take in more tax too.

But there is a key reason beyond sentimentality that people from non-London choose not to move to London: almost all of that extra money earned would be lost through higher housing costs.

The IFS estimates that the average worker in London earns 14% more than the average worker across the country. But when you take housing costs into account this gap collapses to just 1% more.

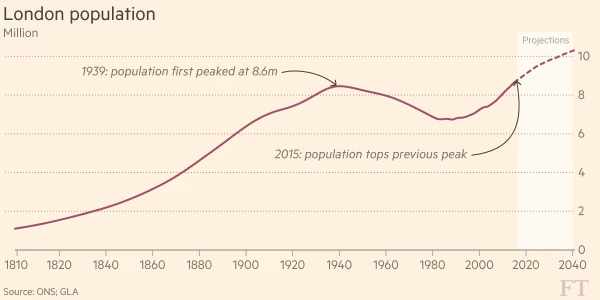

London’s housing crisis is Britain’s productivity crisis. And why might this have had a peculiar effect specifically after the year 2008? Well it could be thanks to one fascinating coincidence. London’s population first peaked in the late 1930s, and didn’t recover that same population level until the 2010s.

This is important, because in the postwar years a huge array of restrictions were placed on how cities like London could grow. A green (grey) belt was established preventing outwards growth. And the discretionary Town and Country Planning Act enabled local objections to often prevent redevelopment and densification within the city itself.

This did not matter so much for productivity growth in London in the late 20th century as the city had already been built to home nine million people. It expanded rapidly through the victorian era right up until the war. As Londoners left after 1939, acute housing pressures were obviously not particularly harshly felt. There wasn’t the demand. That is, of course, until London reached its previous 9 million population again.

This time, unlike before, London’s newly growing population had nothing to grow into. When the population soared before the war, the city was able to grow with it, keeping housing costs low.

Now the population continues to grow but the city is artificially constrained; yes outwards but more importantly upwards too. This lack of supply pushes costs higher and higher, and cuts the real income boost Brits would receive if they moved to more productive jobs.

This doesn’t of course mean an ever expanding footprint of London. Let’s compare actual lived density in London to the centre of cities like Paris or Barcelona, where six or seven storey streets are the norm, tops 50,000 people in one square kilometre (without a tower block in sight). The a beautiful and human gentle density.

Meanwhile in London the very densest square kilometres are home to barely 20,000 people. And the densest areas are places like Marylebone, full of attractive urban six or seven storey mansion blocks, before the war and then Clement Attlee put a stop to it all.

The Chancellor, to her credit, has been one of the most vigorous around the Cabinet table to fix the planning nightmare that holds back so many new homes, roads, railways, power lines, and everything else in this country that is simply too hard to build. But she’s fighting against huge institutional inertia.

It’s not just houses we can’t build

More than the post-2008 London housing problem, there has been a post-2008 infrastructure problem too. Many economists argue that Britain made a bad decision in the post-crash world to not take advantage of the era of low interest rates to build more infrastructure when it was far cheaper to borrow the money to do so.

But this misses a point. The taxpayer spent many billions of pounds on infrastructure in the post-crash era. From HS2 to Crossrail, projects did go ahead. In 2018 Britain was second only to China for rail infrastructure expenditure as a percentage of GDP.

It’s just that in Britain, these kinds of projects are more expensive than just about anywhere else in the world to build. The problem is that our money doesn’t go very far. Not least due to the indulgence of nimbyism that led to the Coalition Government in 2012 to announce miles more unnecessary tunnelling, and the ludicrous Natural England-mandated £125M HS2 bat mitigation tunnel.

I would not envy anyone in the position of Chancellor today. But there is one key area of the economy this newsletter has studiously ignored, an area that undoubtedly has made the lives of the occupants of Number 11 Downing Street utterly miserable for at lest the past half decade. It will be the subject of my next newsletter here on Substack. How the amount of energy we produce has coincidentally collapsed since 2008 too…