Today, the NHS turns 75 years old. As children are made to sing for their healthcare system, and political party leaders attend a literal religious service for it - it’s time to reflect upon 75 years of alternative facts, conspiracy, and outright paranoia.

Despite many colleagues in the British media often professing to be very concerned about the malicious influence of fake news, one area of policy discussion where there is not just a consistent blind spot but often an eager indulgence of the most bizarre conspiracy theories and outright lies, is British healthcare.

From the foundational myth that the Conservatives opposed the introduction of universal healthcare (the original white paper was introduced by Conservative Health Secretary Henry Willink) to the idea that outsourcing cleaning services is part of some fort of sinister plot to begin charging people for their operations (do I even have to explain this one?), the myriad lies, half truths, and misdirection is positively head-spinning to any dispassionate rational observer.

The myth of “NHS spending cuts” is perhaps the most widely believed false meme in this discussion. Take a Sky News report this morning, which pushed out a news alert to millions of smartphones claiming that the “Health Secretary denies spending cuts are behind NHS woes”. Clearly implying that there have been NHS spending cuts.

The article itself went on to claim, under a banner ironically proclaiming “Why you can trust Sky News”, that “The health secretary has refused to accept Conservative spending cuts have played a role in problems faced by the health service”.

Shall we have a look at those spending cuts in full? Adjusted for inflation?

With the exception of aberrant pandemic spending years, health spending has risen every year the Tories have been in Downing Street. And it’s risen faster since the Lib Dems left government.

Compared to 2008/09, real terms annual spending in 2023/24 is up from 121.5bn to 182bn: an astonishing inflation adjusted increase of 50%.

Indeed, as an aside, at the time of the EU referendum, health spending in the UK was £141.1bn. This year’s spend of £182bn - again all inflation adjusted - represents an increase of £40.9bn. That’s not a weekly figure of £350 million more, it’s £787 million extra every week.

Yet these facts do not stop otherwise professional news outlets claiming that the NHS has been “cut”. Despite knowing that it has not been. Sky’s very own article which led with these alternative facts of “spending cuts”, went on to evidence its claim by citing a King's Fund report from April which highlighted “much lower funding increases” since 2010.

It should not take a genius to work out that “much lower funding increases” - funding increases that were nevertheless in every year above inflation - are not the same by any reasonable definition as “spending cuts”. Yet senior journalists will happily describe them as such. It’s hard to think of many other provable falsehoods in British politics so widely accepted as the lie that ‘the NHS has been cut’.

More rational individuals avoid language around “cuts” and focus instead on the more amorphous word “underfunding”. What do they mean by “underfunding”? Funding that is growing in real terms, even in real terms per capita, but not by as much as say an ageing population would demand.

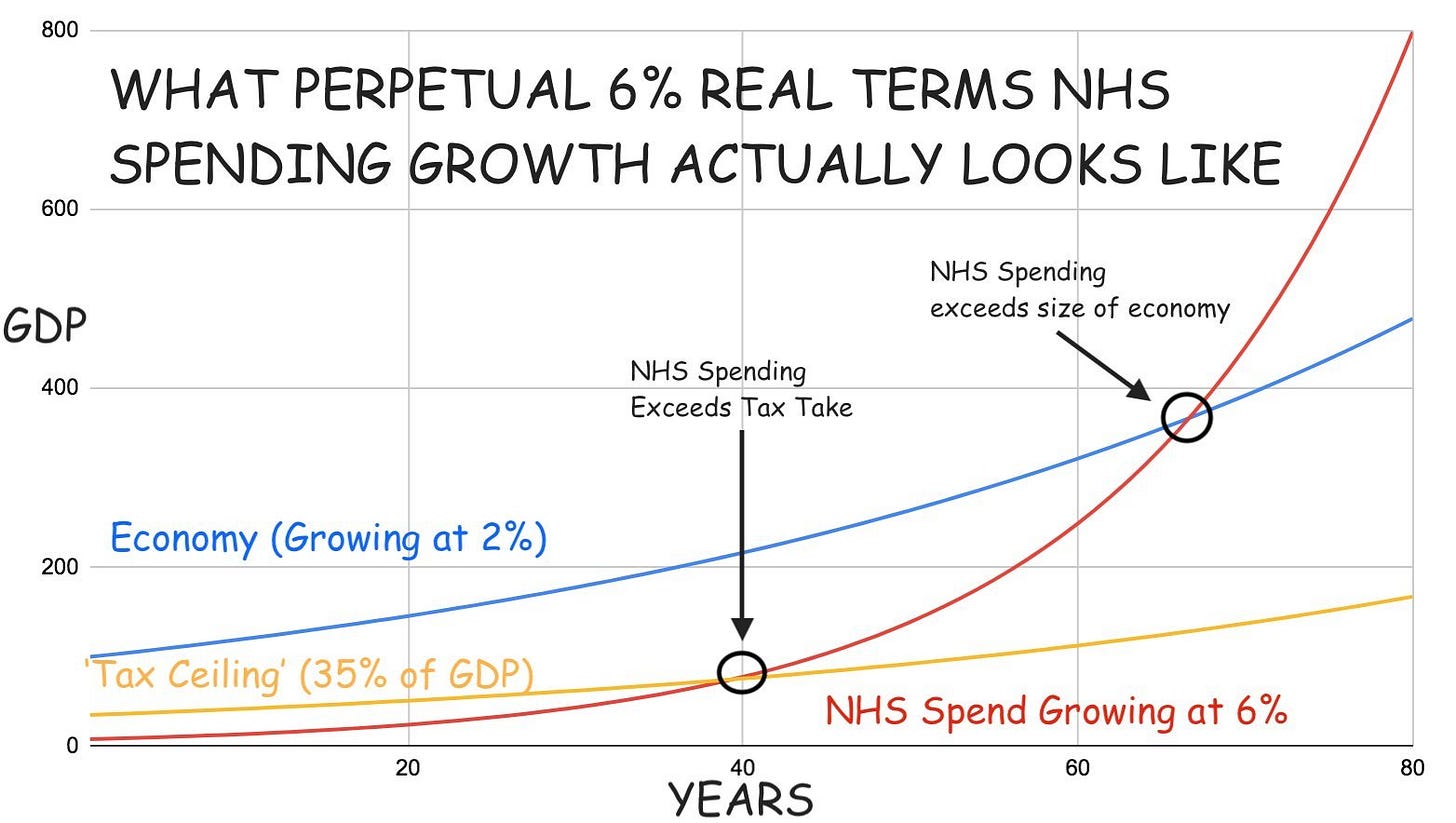

One common refrain is that NHS spending should be rising by 4-6% every year, as it did under the New Labour government, just to keep up with increasing demand. The argument goes that any increase less than that sort of spending boost must be considered a cut. It’s an interesting point of view, but one that gets fairly silly fairly quickly.

A few years ago I got out my crayons and mapped what NHS spending growing by 6% year on year on year would actually look like, assuming - optimistically - that our economy would grow at a steady 2% a year, and 35% of GDP would be collected in tax. After a few decades, NHS spending eclipses the entire tax take of the country, and after a few more NHS spending exceeds the size of the entire economy.

I should not need to explain how bonkers this all is.

Some might argue that NHS spending obviously shouldn’t rise by 6% every year forever - as my comic sans graph maps out - but only for a defined period of time. If that is the case, what is that period of time? At what point can the NHS stop receiving 4-6% spending increases year on year on year? Nobody seems to say.

Perhaps big big spending increases should only last until the NHS is funded to the same tune as its its counterparts in wealthy countries? That’s a complicated question. By some measures it already is.

Here is health spending across a series of relatively rich countries as a share of GDP in 2019 according to the world bank:

United States 16.77%

Germany 11.70%

France 11.06%

Canada 10.84%

United Kingdom 10.15%

Netherlands 10.13%

Denmark 9.96%

Australia 9.91%

New Zealand 9.74%

Italy 8.67%

Israel 7.46%

Ireland 6.68%

(It’s worth remembering here that health spending in the UK has risen considerably since 2019, and GDP has not. Just bear in mind that annual health spending in the UK in 2019/20 was £156bn. This year it has reached £182bn. An increase of almost 17%. I would not be surprised if when the world bank updates its figures, the UK has climbed up the leaderboard.)

Of course, percentage of GDP figures aren’t always the best to use - just look at distorted tax haven Ireland, or the fact that a country can rise up this leaderboard if it is in recession and simply freezes health spending.

So we can also look at the level of health spending per person (2021), priced in dollars - compiled here by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Britain’s health spending is of course well above the OECD average.

Notably, Australia - the country most touted by many British doctors as one they are considering moving to - spends less in tax and mandates than the UK. The difference is made up by a much healthier private sector.

This takes us to a fundamental and underreported fact about universal healthcare systems in other countries - universal healthcare systems that British doctors appear so keen to move to: they are not as state controlled as the British system.

In Australia’s mixed public-private (but nevertheless universal) system, everyone is covered by medicare yet private insurance is actively encouraged for some to ease system pressures overall. Those on higher incomes face a tax penalty if they refuse to take out private insurance.

Australians earning over $90,000 are lumped with a Medicare Levy Surcharge if they do not take out private hospital insurance. The surcharge is designed to encourage individuals to take out private hospital cover, and to use the private hospital system to reduce demand on the public Medicare system.

Compare this to the media hysteria that faced Rishi Sunak when he “admitted” he had used private healthcare cover in the past. Heaven forfend a multi millionaire foot some of their own bills. This incentive structure allows state spending on healthcare in Australia to be lower than in the UK, while total spending is proportionally higher.

Similarly, the government/compulsory spend on healthcare in the UK is not particularly distinct from that seen in France or Canada - another two countries with much greater private cover of those who can afford it, and consequently less pressure on the system for those who need it.

It’s interesting to note how so often the same healthcare unions that rightly highlight how much more competitive healthcare pay is in countries like Australia, are the first to protest any suggestion that anything at all could be learned from how other universal healthcare systems work. Perhaps medical professionals in these countries are able to be paid more competitively thanks to the differences in their systems.

Yet whenever even the most mild change is proposed to how the NHS is run, an incredibly powerful lobby of unions, politicians, and journalists who should know better spring into action to raise the alarm bell of ‘Americanisation’.

As Kristian Niemietz has noted in his excellent paper Repeat Prescription? The NHS and four decades of privatisation paranoia, the same story has been repeated for decades:

“In 1980, an article in The Times predicted that over the next five years, the National Health Service (NHS) would be privatised step by step, and the UK would drift towards an American-type healthcare system. This obviously did not happen. But that has not stopped people from repeatedly making the same prediction ever since.”

Time and time again not just fringe oddballs but mainstream bodies, publications, and politicians have advanced the bizarre conspiracy theory that sinister forces are desperate to rip away the universal principle underlying the health service. We are continually told this is just around the corner and yet mysteriously it never occurs. In this sense The Guardian and its like could be compared to apocalyptic preachers, warning “the end is nigh”, ad infinitum.

It should be noted that while the UK was third in the world to arrive at the universal principle after Prussia and Norway, it was certainly not the last to deliver it. Indeed over the last 75 years every single other developed country in the world has arrived at a form of universal healthcare - save for one notable obnoxious exception.

Despite this there are some who remain convinced that the worst-of-all-worlds American system is one a secret cabal of Tories are desperate to foist upon the United Kingdom. Election after election we are told by left wing parties and papers that “We have 48 hours to save our NHS” (Mirror 10 October 2011), “We have just three months to save the NHS” (Ed Miliband 4 February 2012), “Just 52 hours to save our NHS” (Mirror 5 May 2015), “Stop Brexit to save our NHS” (LibDems 15 September 2019), “Boris and Trump plot NHS sell off” (Mirror 31 October 2019)…

Yet the NHS is still here. Astonishingly, the Americans did not buy it. And astonishingly, a centre-right1 party winning an election on a manifesto of putting a lot more more money into the NHS did not suddenly reverse ferret and throw both the NHS and any chances of being re-elected into the metaphorical dustbin.

To continually evoke the bonkers American healthcare model is diversion tactic of people who simply cannot imagine a world with more than one way of delivering universal, free at the point of use healthcare. It is deployed wittingly or otherwise to ward off any real discussion about sustainable health system reform.

In the midst of this absurd theatre, a dispassionate observer might wonder how the UK could engage in a productive conversation about the future of healthcare. How could we learn from other countries, say from the Netherlands or Australia? Sadly, for now at least it seems we're stuck with an endless loop of straw men, alternative facts, and conspiracy theories that distract us from having a thoughtful conversation about healthcare policy that isn’t filled with misinformation or paranoia.

So as the bells of Westminster Abbey chime in a peculiar service for our strange symbol of modern Britishness, here’s to hoping that the next 75 years of healthcare discussions involve less superstition and blind faith. Here's to hoping that future debates rest on the grounds of greater logic, reason, and evidence. Well, a man can dream. Perhaps we just prefer the pantomime.

Centrist? Centre left? It’s hard to tell any more.