Great Elexpectations

Or a Tale of Two Populists

“it is the desire of the present possessor of that property, that he be immediately removed from his present sphere of life and from this place, and be brought up as a gentleman - in a word, as a young fellow of great expectations.” - Charles Dickens, 1861

The last four days played host to two elections in either corner of the Atlantic Ocean. One, more meaningful and the other indicative. I am, of course, writing of the crucial mid term elections in Argentina, and the marginally less crucial Welsh Senedd by election in Caerphilly. I’ve written before about the policy substance of Milei and Farage. Now it’s time to examine electoral tactics.

Both elections were seen as milestones for the advancement of two different flavours of right populism. Over in Argentina, Javier Milei was at risk of floundering. He was desperately in need of electoral success so investors and speculators could see his reform agenda as sustainable.

When local elections in Buenos Aires at the start of September saw opposition Peronists over-perform and beat Milei’s La Libertad Avanza by more than 13 points, markets tanked. Investors feared Milei’s reforms could be halted, or even unwound. Consequently the stock market plunged and there was a run on the peso.

While gleeful left wing commentators began to claim this meant Milei’s libertarian agenda of slashing spending, eliminating more than half of all government departments (eighteen down to eight), and deregulating sector after sector of the Argentine economy, was a failure - in fact it showed the opposite.

The very fact of markets becoming wary when Milei’s party faltered, showed implicit market support for his reforms - rather than the opposite as some disingenuously claimed. The real risk highlighted by last month’s local elections was that in yesterday’s crucial legislative mid term elections, La Libertad could retreat. That the statist Peronists could win. The market concern was over the possibility that Milei could have been neutered.

The stakes for Argentina were enormous. Milei couldn’t simply perform adequately. He had to be seen to win. He had to be seen to carry the confidence of the electorate. He had to reestablish political momentum to push through his reforms, and push on to roll back the frontiers of the state.

For the Milei project to be sustainable he has to establish momentum to carry through politically fraught reforms to tax, pensions, and the labour market. Given electoral arithmetic in the Chamber of Deputies and Senate, coalition building is crucial to pass sweeping legislation.

This is clearly why the game of expectation management was so important. To win a greater share of votes than expected is to deliver not just seats but political momentum. To win by more than expected is to deliver the all so crucial confidence that Milei was so desperately in need of. It’s the result relative to expectation that matters almost as much as the result itself.

Perhaps that’s why, as reported by The Guardian:

“The government itself had downplayed expectations, considering anything between 30% and 35% a satisfactory outcome, especially after Milei’s heavy defeat in September’s Buenos Aires provincial elections, when he lost to the Peronists by 14 percentage points.”

In the end, Milei won 41% of the vote, seven points clear of the left wing coaliton, doubling the number of seats La Libertad held, and providing the President with enough deputies to protect his veto power from being overridden by Congress.

But the mood music is just as important. Remember, when markets lost confidence in Liz Truss to deliver any spending reduction at all she nominally commanded a majority of 64 in the House of Commons. What she lacked was the political authority, and some might say backbone, to drive through any spending reductions at all.

Strategists at La Libertad Avanza knew that whatever the election outcome, their political project withered or thrived on the back of confidence. And so they managed expectations, arguing even 30% of the vote would have been a victory. This made victory all the more impressive, impactful, and sustainable when it arrived.

Meanwhile in Wales…

Here’s a story lost in the melee: The Reform Party performed extraordinarily well in Caerphilly. The seat, nestled at the foot of the valleys, has been at the heart of the Labour Party and its wider movement for more than one hundred years. It’s just down the road from Merthyr Tydfil, the former seat of Labour’s first leader (and the current Prime Minister’s namesake) Keir Hardie.

For Labour to lose this seat is more than a political earthquake. It is to undo the consistent results of more than one hundred years, and reveal a significant Scotland-style hollowing out of the vote in Labour’s traditional heartlands.

While the Reform Party did very well, however, it was not the movement to dislodge Labour after all these years. That privilege fell to left wing nationalists Plaid Cymru.

Headlines like “the Reform backlash”, “we now know how to stop Farage”, and “Blow For Nigel Farage As Reform UK Fail To Win Key By-Election” abounded.

Lindsay Whittle, the winner of the seat, had stood in the area fourteen times unsuccessfully - at every general election since 1983. “That’s more times than me!” quipped Nigel Farage today as he attempted to explain Reform’s failure to win the seat despite sky high expectations.

Farage reeled off the lines; Whittle was a well known figure locally, more so in the heart of the constituency. In the centre of Caerphilly, they practically had to weigh the Plaid vote.

It was difficult to see Farage’s comments today as anything other than being on the defensive. He had in the days leading up to the by election instead seemed supremely confident. He did nothing to dampen speculation. No Milei-style expectation management.

In one way it’s uniquely difficult for an upstart party with barely a handful of MPs. They have to portray confidence to the electorate. They have to establish in the minds of the voters that they can win, just to get a hearing. Something older more established parties rarely have to think about.

And yet here lies the bear trap. Whilst Reform has to prove itself a contender to get a hearing, too much bravado spills over into hubris. And sets the party up for a fall.

Suddenly an impressive showing in a Labour heartland stops being a ‘wow’ moment. An extraordinary share of the vote for an upstart right wing party, that at once is able to be spun as a defeat. Expectations made Milei look like a winner, and those same expectations helped make Farage look like a loser.

I can’t quite believe I am writing this, but perhaps Nigel Farage should take some lessons in humility from the man with the famous chainsaw, who spent the early hours of this morning singing “I am the king of a lost world”.

Gulliver returns…

Now aside from expectation management either side of the Atlantic, it’s worth noting that the Labour Party surprisingly has a lot to be cheerful about in its historic defeat. I’ve written in these pages before about Gulliver Theory, which I explored back in May.

While Reform leads by a considerable margin in all the polls, its 10 point lead is less significant when looking at the divided opposition. Up to 20 points for Labour and the Tories apiece. Up to 15 points for the Greens. And double digits for the Lib Dems too.

While Reform is towering up to 35%, all the parties opposed to it make up at least 65%. The real question for Reform is in how many seats will Labourites, Lib Dems, and Greens and the like hold their noses and vote for the candidate most likely to keep Farage from Number 10.

It appears as if this was a significant factor in Caerphilly.

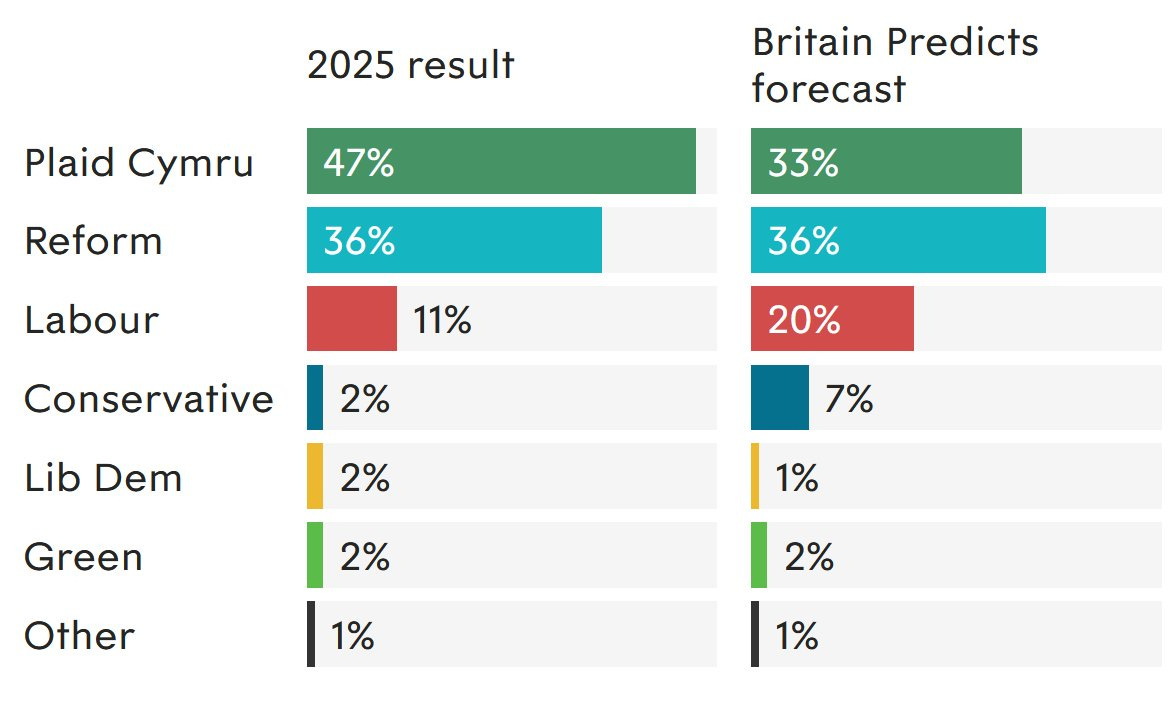

The ordinarily scarily-reliable Britain Elects forecast (Britain Predicts) got the Reform vote share in the constituency absolutely bang on. However, it predicted a Reform gain. What happened? The other non-Plaid parties underperformed relative to the model.

Labour was squeezed to around half their predicted vote. The Lib Dems halved again. For the Tories they won just a sixth of their expected vote share.

It’s easy to see what might have happened here. Labour, Lib Dems, and some centrist Tories likely decided they cared more about stopping Farage than they did about backing their preferred candidate. This is something polling finds almost impossible to predict. And is something that even the fancy pants and increasingly popular Multilevel Regression and Post-stratification (MRP) statistical modelling technique struggles with.

In short, it means a ten point lead at 30 or 35% cannot be considered with the same reliable predictability as a ten point lead at over 40%. The lead will be different against different parties in different parts of the country.

But in this confusion also lies an opportunity for Reform. As the former Number 10 pollster James Johnson wrote this weekend in the Telegraph:

Even if the Lilliputians had restrained Gulliver in Caerphilly, it would be harder for them to do so in a general election. It is less apparent who the leading parties are in a specific seat at a general election, especially one in which one in every three seats will be marginal and scores of them are set to be genuine three-way or four-way marginals. In some seats, two or three or even four parties will be claiming to be the entity best positioned to beat Farage.

Nigel Farage’s salvation may lie in the utter confusion as to who leads where. And thanks to one unlikely bedfellow: the new Green Party leader Zack Polanski.

If the Greens and their impressive polling surge (delivered through the sort of banal left wing platitudes you might expect to hear at a student union) radicalise a portion of the left, it might be Nigel having the last laugh.

Assuming enough Labour voters are sufficiently convinced that Keir Kapitalist Starmer is truly as evil in their eyes as the ‘nasty Tories’ and ‘fascist Reform Party’, those former Labour voters even holding their noses would not be able to hold back the stench of a sufficiently pungent Labour Party.

If enough voters are convinced that the bond markets aren’t real, that Billionaires can’t move jurisdiction, and that tax rises have no dynamic effects on an economy - well any fiscal restraint at all looks frankly callous. And in the eyes of the Polanski acolytes, what moral person could bring themselves to vote for a callous Prime Minister, even if that does risk letting even a hubristic Nigel Farage saunter into Downing Street in 2029?